Red Vienna: A worker’s paradise

During the 1920s and early 1930s, “every visitor to Europe who had any interest whatsoever in reform, housing, social progress, went as a matter of course to look at the magnificent workers’ apartments that Vienna had built,” the distinguished American journalist Marquis Childs observed. Between 1923 and 1934, the city’s socialist administration launched an extraordinary campaign to provide housing for working-class residents, who were among the party’s most enthusiastic backers.

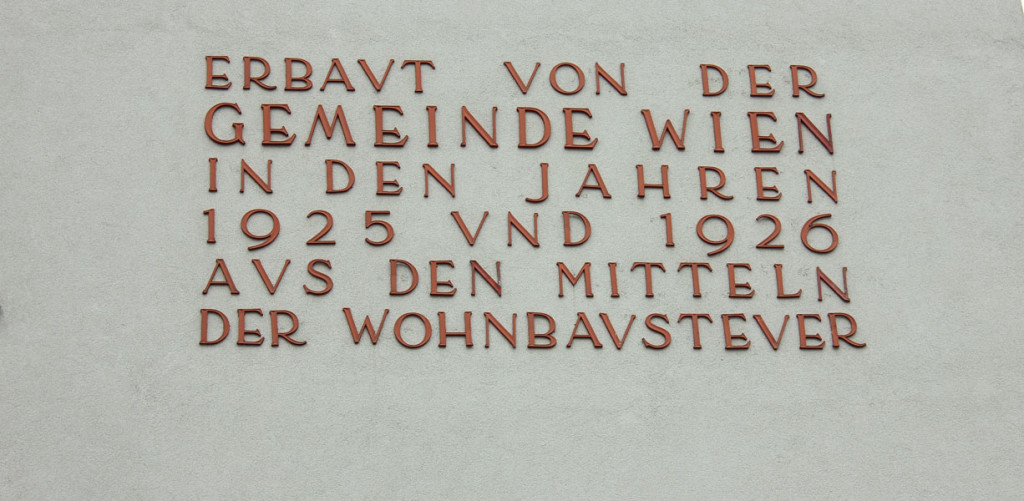

The government constructed 400 apartment complexes–64,000 new apartments in all–that together housed one-tenth of the city’s population. The pride of Vienna’s residential-building program was the majestic Karl-Marx-Hof (Karl Marx House), designed by Karl Ehn. Stretching almost a mile along a major railway line, the Karl-Marx-Hof featured five monumental archways, a striking red and yellow stucco facade, and lush interior courtyards as well as state-of-the-art kindergartens, playgrounds, maternity clinics, health-care offices, lending libraries, laundries, and a host of other social services.

As their heroic scale suggests, the Wiener Gemeindebauten (Vienna Communal Houses, as all of the new socialist apartments were called) amounted to far more than mere residential housing. They embodied something more politically daring and potentially fragile. As Eve Blau points out in her handsomely illustrated and well-researched study, The Architecture of Red Vienna 1919–1934, the communal houses were a vivid expression of the working class’s ascent to power. The heady symbolism of the houses did not go unnoticed by the regime’s rightist opponents. As Blau observes, socialist housing went up in “the midst of highly charged, and often violent, political conflict between right and left.” During the civil war of February 1934, “Red Vienna” came to a sudden, tragic end, as the socialists’ enemies fired on the Karl-Marx-Hof and drove the party and its leader’s underground, often into exile.

Red Vienna had its beginnings immediately after World War I, when the Austrian Social Democrats, whose leaders included such remarkable “Austro-Marxists” as Otto Bauer, Karl Renner, and Max Adler, inherited power and established a new republic. Against the backdrop of severe food and housing shortages produced by both the military defeat and the collapse of the monarchy, the Social Democrats won a significant electoral victory in the municipal elections of May 1919, making Vienna the first major European capital to be governed by an absolute majority of socialists.

The socialists’ triumph was short-lived. Just a year after taking power in Vienna, they were defeated in national elections by the agrarian Christian Socialist Party, which whipped up anti-socialist and anti-Semitic sentiment among rural voters. Excluded from power at the national level, the Social Democrats in the city council eagerly turned Vienna into their laboratory. There they had virtual sovereignty over decision-making, thanks to a 1921 constitutional provision that made Vienna an independent province. It didn’t take long for Red Vienna to become the interwar period’s most extensive European experiment in municipal socialism, and perhaps the most ambitious such experiment ever.

Vienna’s communal houses were both a symbol and a strategy. As a symbol Red Vienna offered “the best object lesson in the world of what Socialism can and cannot do on a democratic basis in a Socialist capital of an anti-Socialist State,” the British journalist G.E.R. Gedye noted at the time. The Viennese workers’ houses were islands of socialist power in a bourgeois city. With their monumental facades and their entrances accessible only from interior courtyards, the Gemeindebauten resembled citadels: While their existence challenged the old order, they were confined to enclaves that betrayed the party’s political vulnerability.

Vienna’s apartment blocks were also a key component of Social Democratic strategy. The Austro-Marxists believed that by building municipal socialism they were laying the foundations of the future socialist society. A “pragmatic utopia” that comprised an extensive network of educational, social, and cultural institutions, the housing program fulfilled the immediate needs of workers while converting them into socialist citizens. In the words of Otto Bauer, the party’s leader and most brilliant theorist, Red Vienna fused “sober realpolitik and revolutionary enthusiasm.”

The socialists’ housing projects drew fire from rightist critics, who assailed the workers’ houses as “voter blocks” (their very size transformed entire districts into Red precincts) and as “fortresses” destined to hold hostage key bridges, railways, and sewer lines. But there were also complaints from friendlier quarters. A number of Vienna’s most innovative architects, including Josef Frank, Margarete Lihotzky, Franz Schuster, and the eminent Adolf Loos, all of whom worked for the administration, took the city building agency to task for failing to produce a unified aesthetic vision. In their view, Vienna suffered by comparison with the sleek, modern satellite towns built outside of Berlin by Martin Wagner and outside of Frankfurt by Ernst May. (Ironically, some of the most impressive Frankfurt projects, like Lihotzky’s famous “Frankfurt Kitchen,” were designed by Viennese architects whom May had wooed for his housing initiatives.) In 1926, the German city planner Werner Hegemann gave voice to conventional wisdom when he pronounced Vienna a “missed opportunity.”

Echoes of such criticisms could be heard in the influential work of the Italian architecture critic Manfredo Tafuri. In his 1980 study Vienna Rossa, Tafuri, a Marxist, described Red Vienna as a “declaration of war without any hope of victory,” condemned to failure by the contradiction between the Social Democrats’ radical rhetoric and their reformist strategies. The communal houses, he argued, were, like Red Vienna’s socialist administration, “petit bourgeois” and structurally incoherent.

Blau’s book is an important corrective to these harsh evaluations. Like Tafuri, Blau sets the communal-housing program in the political context of Austrian socialism’s historic compromise with capitalism. But she does not write about Red Vienna’s architecture as if it were simply a mirror of the troubled Viennese political scene. Instead, she focuses on the city planners and architects, coming up with a different set of answers to the question of what was unique about Red Vienna and why its heterodox style departed so dramatically from the architectural experiments in Germany.

Though socialist ideology influenced Vienna’s housing program, Blau shows that practical constraints ultimately determined the sites and structures that were built. Among these constraints were a depressed housing market, strict rent controls, and an exorbitant tax on luxury apartments. To make matters worse, the end of World War I plunged Vienna into an acute housing and food shortage, setting off potentially dangerous levels of social conflict. There was a sizable and radical squatters’ movement, and settlements were springing up on unoccupied land at the outer edges of the city. Faced with a movement of unemployed settlers and a massive housing shortage, city officials initially considered building “flourishing garden cities” of the kind promoted by renowned architects such as Heinrich Tessenow and Loos, who was made director of the city’s settlement office.

Loos’s vision of self-sufficient garden cities on the outskirts of Vienna proper fell out of favor with planners, however, when it was discovered that Vienna’s status as a province would prohibit the city from acquiring new land or expanding beyond its pre-1921 borders. The workers’ housing program inaugurated that year was thus restricted to sites either owned or bought by the city and with easy access to existing railway, bus, and tram lines. As a result, the socialists decided to concentrate housing in urban complexes.

Lacking a firm architectural or town-planning vision, the city enlisted several students of Vienna’s most prominent prewar architect, Otto Wagner, who is now best known for his Postsparkasse (Postal Savings Bank), to design large-scale public housing. The city building agency, Blau argues, “favored a neovernacular architecture,” and Wagner’s students, notably Josef Hoffmann, Hubert Gessner, and Karl Ehn, seemed best qualified to create it, despite their lack of socialist credentials.

What Blau calls “Wagner School Practice” was not so much a distinctive style as it was a “strategy of architecture”– a way of thinking about the social uses of buildings. Red Vienna’s housing complexes placed less emphasis on private space (apartments were notoriously small) and street access in favor of semi-public spaces and interior courtyards. By retaining the old city plan, the socialists honored the older, bourgeois topography. At the same time, they transformed the bourgeois notion of private interiors by adding such public facilities as playgrounds and laundries.

The socialists’ predilection for courtyards and monumental facades highlights not only their belief in the social function of architecture but also their sensitivity to the cultural memory of Habsburg architecture in the Baroque era. An especially striking example is the Reumannhof, a major complex named after the city’s first socialist mayor, Jacob Reumann. With its large central court flanked by smaller side courts in the Baroque manner, the building alluded to the Shoenbrunn, the nearby imperial summer palace.

Although Blau appreciates monumental “superblocks” like the Karl-Marx-Hof and the Reumannhof, which feature a “historical” and “embellished” Wagner School Modernism, her aesthetic sympathies lie with the more marginal projects that she calls “countertypes,” notably the Winarskyhof, jointly built by Peter Behrens, Josef Frank, Margarete Lihotzky, and Adolf Loos. Diverging from both Wagner School monumentality and German functionalism, such buildings achieved a more complex balance of tradition and modernity, and a greater diversity of color and detail.

While the architecture of Red Vienna still stands today, the ideas that animated it, and the politics it embodied, have largely vanished. As Blau writes, when the guns of the fascist paramilitary fired on the Karl-Marx-Hof in February 1934, “it was the idea, not the buildings, of Red Vienna that they destroyed.” Indeed, several of Red Vienna’s most prominent architects, notably Ehn, went on to design buildings for the Nazis, a sad coda to the socialists’ defeat.

By devoting close attention to Red Vienna’s built environment, planners, and architects, Blau has shifted discussion from the polemical arguments of socialist leaders to the way in which the Gemeindebauten successfully “established a new relationship between private and public space… in Vienna.” She argues cogently that Wagner School Modernism was at once socially progressive and respectful of Viennese traditions. And she explains deftly why this style fit so well into, and has continued to complement, the city’s spatial patterns. Still, she fails to answer the larger question that her book raises: Why does Red Vienna continue to figure in architectural discourse so long after the political and military defeat of its ideas? Did its idiosyncratic blend of large-scale housing construction, Wagner-style Modernism, and visionary socialism turn out to be a success after all?

Article Author: Anson Rabinbach

Professor of history and director of European Cultural Studies at Princeton University. His recent publications include: In the Shadow of Catastrophe: German Intellectuals between Apocalypse and Enlightenment (University of California Press, 1997) and The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue and the Origins of Modernity (Basic Books, 1990).

Source: www.metropolismag.com